Incredibly, it was only after the success of the single that Philips awoke to the cause. Incredibly, it was only after the success of the single that Philips awoke to the cause.

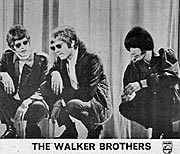

David Shrimpton was head of Philips stock control but up until now The Walkers had merely registered as three more pretty anonymous faces.

“With regard to what The Walker’s were doing earlier on, I really don’t know,” he admits, “I may be over emphasising this but they were signed to Smash/Mercury in the U.S not Philips UK. The deal and their ownership of recordings belonged firmly with those in the USA. However, after ‘Love Her’ people in the office began to take notice.

My first visual impression of them was that they were quite tall with skinny arms. They were also very aloof and seemed humourless with the exception of Gary.

They didn’t really mix with the staff at Philips and kept pretty much to themselves”.

John: “We came over and we went to see the people at Philips records…and we all said ‘Hello’ and they said ‘hello’ – and everybody was polite. We said ‘We’re going to be in town for a few weeks. We’re just going to cruise around and look at England’. They said ‘Ok’. I guess about that time they sent the ‘Love her’ tapes over to Philips. The next time we called them up – actually we didn’t call them up, they called us up and they said ‘we want to talk’! So we said ‘Ok’ and went to their office. Then all of a sudden we noticed there was a lot more brass in the room, y’know. The first time we went it was like a secretary and somebody else. The next time it was like the vice president of the company…”

By the time Gary, Scott and John had exited the meeting at Philips, their world had changed irrevocably. The Bedsit was the first to go, and Scott and Gary (with the latter’s’ train set) moved into a furnished flat in Chelsea. Visiting journalists were immediately introduced to the Dadaesque surroundings of their new home. The flat apparently came with an anonymous marble bust, a giant Aspidistra, a bedroom adorned with 15 mirrors and an out of work actress who improvised as their secretary,

Holding court, Gary was an interviewers dream. Buzzing with nervous happy energy he hopped from subject to subject regardless of the question. When Gary got going he was like a Yorkshire Terrier on Speed.

“John… kept coming back to (Onslow Gardens) at ridiculous hours in the morning and the landlady was going out of her mind and everything. He would insist on playing this one guitar run at about 2am, so we decided to compromise and left”.

“We got this new road manager, Claude Powell just over from the States. He doesn’t know how wild the fans are over here, see. We went to TOTP in Manchester and outside were about 75 kids. Claude’s famous last words were ‘Don’t worry, I’ll hold them back’. He lost his cuff links, his watch, his jacket…they did the Mash Potato all over his face”.

The enigmatic ‘Claude Powell’ was also named as their ‘mysterious backer’ during early interviews. (The backer was of course, Gary’s Step dad) and Powell would exit their story as quickly as he entered it, leaving the ethereal traces of a fantasy character, most likely made up by the boys for amusement during one long February afternoon in bed sit land.

With chart success and new digs came substantial professional allies. In signing to Capable, the boys now had heavy management who in turn arranged an agent; (the prestigious Arthur Howes), while press was initially managed by established publicist Brian Somerville. In finally signing to Philips (who bought out their contract with Ben Ven/Smash) they acquired a powerful label that was beginning to plough its considerable resources into their cause.

By adding the combined might of these advantages to their all - American good looks, Scott’s voice, the combined chemistry and charisma of all three, and all of this caged within the Pop Epoch of 1965…

Success was begging them and the Philips recording studio was wide to receive.

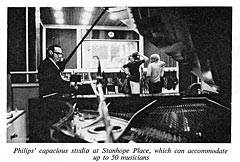

As Abbey Road was to EMI, so the ‘In -house’ studios at Stanhope Place, Marble Arch was to Philips.

Situated on the cusp of London’s heart and above the central line – a faint rumble could be felt as the tube passed below – during it’s 30 year existence, the Philips studios would easily rival America’s Stax studios or London’s Abbey Road as a ‘Hit factory’. Situated on the cusp of London’s heart and above the central line – a faint rumble could be felt as the tube passed below – during it’s 30 year existence, the Philips studios would easily rival America’s Stax studios or London’s Abbey Road as a ‘Hit factory’.

The list of those who recorded there is eclectic and comprehensive, and includes practically everyone who was anyone, chart wise, between the 50’s and early 80’s.

At 60ft long, 20ft wide and 25ft high, the main studio, ‘Studio One’ has been described as ‘cramped’ by one engineer who routinely recorded full orchestral and choral sessions there and as ‘Vast’ by The Who’s Roger Daltrey who recorded there as part of a four piece.

Session guitarist maestro Alan Parker was among one of the new recruits called in for The Walkers first session.

“The studio was a little bit confined, long and narrow and the control room had like a narrow walkway at the back where we used to stand and listen, you know. So it was a bit restrictive, with all the orchestra and brass, percussion and singing groups…it was really crammed in”.

Entrance to the studio reception was down a stairwell via the street, in through a side door, turning left to go up. The actual recording space was on a raised level.

The guts of the studio were typical of the time.

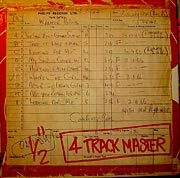

Roger Wake, then a teenage tape Op’ remembers the studios specifications with a boffin’s clarity. “Physically the set up was this; there was the studio, then the control room, and then a separate machine room, where the tape machines were. The control room had big windows so that Johnny (Franz-producer) and Peter (Oliff –Engineer) could look out and see into the studio and from where I was, in the machine room, we had a little window about 3ft square, so I could see into the control room. We also had a set up so that I could hear what was going on in the control room. If Peter wanted to speak to the studio or me, he had a talkback button for both. So I’d be in the control room with all the tape machines, the multitracks and the stereos and big huge patch panel, which we would have to operate. And Philips then had a totally different patching system to other studios such as Abbey road. Huge plugs - send and return within the same plug. The patch panel was about seven by four feet. Of course, it was all valves back then. The first Neve console was transistorised but the first time The Walker Brothers would have recorded in England it would have been on an old German valve console. On four track.”

Keith Roberts was a budding arranger and a regular at the studio, and although he wouldn’t work with John and Scott for a few years yet, he was familiar with the placing of musicians at such a session.

“The strings right down the far end, usually. Drums in the middle. So both sides could hear them. The other rhythm stuff was around the drummer. The guitars and the Bass guitar. I’d be in the middle, conducting. So all the musicians could see me. You’d have headphones on-one ear on one off…”

The human embodiment of the Philips studio was the aforementioned producer - Johnny Franz.

Mr Franz, addicted to (sugarless) cups of tea, dapper in a deep grey fifties style pinstripe suit, dark brown hair slicked back, his groomed moustache pencil thin, always seemed to have one hand in his pocket, while in the elegant piano player fingers of the other, a cigarette perpetually burned, swathing him in smoke.

Dave Dee, who was at this time tasting first success with Dozy, Mick, and Titch recalls Franz with a cinematic clarity. “He used to smoke like a trooper. I mean, I been to his house for dinner and everything – he was a lovely bloke, Johnny – but we used to sit and talk to him and he used to sit and smoke a fag while he was talking and we used to time how long it took before the ash fell off. He used to sometimes smoke a cigarette almost two-thirds with the ash still on it. He would be talking, and he’d get engrossed with whatever it was he was talking about, whether it was music, or whatever…and the ash on the end of his fag used to get longer and longer and longer. And it was a standing joke with us, how long he could get down the cigarette before the ash fell off”.

Born in the London village of Hampstead on February 23 1922, Franz was a bona fide Londoner and a naturally gifted pianist, gigging through the Blitz, playing at various nightclubs in the West End during the War.

At some point in his twenties he was involved in a light airplane crash, when the DH Dragon Rapide Biplane he was travelling in up - ended at Jersey Airport. Dazed and in shock, Franz – a passionate amateur photographer - still had the witherall to stagger from the smoke and photograph the wreck. The incident would leave him both with a lifelong fear of flying (he would never fly again) and a slight stoop in his stature.

After serving an apprenticeship of sorts, orchestrating for the BBC and working as an accompanist for singers such as Anne Shelton, in 1954 he was appointed as Philip’s first ‘resident’ producer and A&R man, only one year after the company had formed.

This was a powerful position and although a beloved figure, he was also greatly respected as Roger Wake affirms.

“John Franz wasn’t really known for having any ‘messing about’ moments. It’s not the sort of thing he did. He didn’t really lighten up at all. Certainly from a Tape Op’s point of view, he wouldn’t. He always had a copy of ‘Amateur Photographer’ magazine around as well. He’d be sitting with his legs crossed, reading his amateur photographer and scratching his Balls. Until he accepted you, he was a difficult man to work for. A daunting person occasionally. But everyone loved him”.

Many of the musicians employed by Franz remember him as an encouraging, inspiring benign figure. Although in a position of power, he did not abuse such privileges. It seems he was, at heart, ‘a nice guy’, who was rarely bored and never boring.

“The great thing about Johnny Franz was that he was such a fountain of information, so aware of what was going on in terms of technical innovations and so forth…” States Dave Shrimpton who to this day has Franz’s address book in his possession, admitting to ‘missing him every day’. “When he wasn’t busy buying Harry Seacombe’s old Rolls Royce’s, he would routine songs in his office, which was directly above the studio, and the artists would learn so much about recording from him”.

“He was lucky in a way.” Remarks Dave Dee.” He was a musician who loved music and obviously, he got himself into a situation where he hit producing at the right time. It all came together for him.”

Being an acutely active A&R man, (he had signed both Shirley Bassey and more recently Dusty Springfield, (1) the former after merely seeing her perform on TV), Franz had heard the Walker Brothers before he had seen them. He was apparently under the impression that they were middle - aged crooners and on meeting them was somewhat taken aback by their youth, all three then being barely in their twenties.

The cultural and age differences would ultimately be for the greater good. When the boy Engel looked at Johnny, it seems something clicked. Instantly, a mutual respect and affection sparked up between them. While giving the impression of refined, somewhat old-fashioned gentlemen, Franz was essentially ageless with an appetite for life that did not confine itself to his peers.

Dave Dee was slightly older than Scott but remembers Franz’s graciousness well.

“I was about 22 at the time, and I used to go and sit with Johnny when we was recording. You know, if you’re in a recording session and you’re not involved in some bit of it, the other boys are doing backing vocals or whatever; you’d be sat there twiddling your thumbs. So, I used to wander around the Philips building and sometimes if he was in his office, I just used to wander in and say ‘You got a minute’? ‘Yeah’, and we would sit and talk about anything.

He was short and chunky and I couldn’t place his age. He was older but he wasn’t…old.”

Guitarist Alan Parker:

“From what I ascertained, or ‘Sussed ’as it were, Johnny and Scott always seemed to be very friendly and very collaborative. I’m sure Scott had a lot of respect and admiration for Johnny, he was a very experienced man, you know, he was a producer of a hell of a lot of big artists, you know, there is no hiding from experience. Johnny was a lovely man, actually…and a real producer.”

“Johnny Franz was old school.” Scott told the journalist Joe Jackson in 1995, “A great piano player for singers…He played for Tony Bennett…everyone. A great man combined with Rock ’n ’Roll players and a young engineer(Oliff)... it was wonderful to be with him.”

The incongruous looking duo of Engel and Franz would soon both be working together obsessively and socializing - mixing business and pleasure.

They dined together frequently either at their favourite local Chinese restaurant, ‘The Lotus house’ on Edgware road, and at Franz’s impressive residence near Hampstead Heath, which the producer shared with his wife, Moira. Engel and Franz were both obsessed and possessed by music and clearly enjoyed each other’s company and talent, discussing arrangements, writing songs and playing standards together just for the thrill of it all.

As head of A&R, Franz had a baby grand in his office. Quite often sessions would be delayed as Scott and Franz ran through the classic American songbook. Gary would often sit in as a one-man audience making requests.

“I’d be there, giving ‘em the most obscure numbers I could think of – you know, old standards and such and I couldn’t catch em out - they knew ‘em all!”

The resident engineer at Stanhope place was at this time Franz’s ‘number two’, Peter Oliff, a diminutive man who while at the sound desk, was perched somewhere between Franz and Wake.

Recalling Franz’s right hand man to some decades later, Scott’s comments would provide an insight to what could arguably be thought of as the parallel, if invisible Walker Brothers. A trio consisting of himself, Franz and Oliff.

“(Oliff) was a great engineer” says Scott “and he’d been doing Dusty Springfield and all those people. But although he had a wonderful idea of what a new sound could be he couldn’t quite get it. So I knew what was happening at the bottom end and that’s what made it complete. What Spector did was use two bass, an upright, and an electric. Then he used two or three keyboards playing the same thing. One would be an upright piano and the other a harpsichord. Then he used two, three maybe four guitars. Whereas Peter was just using the basic guitar, bass drums set up with two drummers sometimes.

Johnny Franz could read music whereas Spector couldn’t.”

That summer of ’65 would place the anonymous looking Stanhope place in the role of midwife for what was to be The Walker Brothers debut album.

Now assured of a successful stay in Britain, John Maus had returned to America to marry long time girlfriend Kathy and when he returned to the UK in that first week of July, sure enough, he found a tour and a recording session booked for him.

Being driven to Stanhope place that morning, Scott was nursing a sore Jaw - the result of having answered the door the night before to a drunken stranger who had turned up at the flat claiming it was his house. As Scott started to argue the stranger had punched a bemused Engel in the face. This was no bad omen however and such uncouthness mattered not. Their debut recording session on UK soil was superlatively successful, aching jaw and all. After all, the very first song of their very first UK recording session was ‘Make it Easy on yourself’.

Gary explained the reasoning behind their choice of song:

“Bacharach is writing very well at the moment and he’s quite well accepted, so we liked the song very much and it was down the same lines as what we’d done before with ‘Love Her’. And we thought it would be good all round, y’know. So we cut six sides and out of those six we figured The Bacharach is about the best.”

John had found the song initially.

“Jerry Butler had done it.” He explained. “And I was an incredible Jerry Butler fan. So I kinda’ presented the idea to Scott and said ‘what do you think? Should we have a go at trying this’? You know, it’s a big task. Jerry Butler’s version was so good”.

The arranger for those first sessions was to be one in a long line. Ivor Raymonde was a well respected professional who was best known for some exquisite work with Dusty Springfield. He loved ‘Make it…’ and established an instant rapport with Scott and co.

“Ah! What a joy to record a song like that!” he told London radio 25 years later, “I mean the song itself is beautiful. Putting an arrangement to it is absolutely magic.

Between Scott and myself, we devised an orchestra that would be The Walker Brother’s band - if you know what I mean. So we had three pianos, four guitars, umpteen Latin American instruments, percussion… a sound that we hoped would be the ‘Walker Brother’s ’ - and of course, it worked.”

Although full credit was given to writers, arrangers and producers, none of the musicians who made up this ‘Walker brothers band’ were mentioned on the record sleeves. They were, as a rule paid ‘on the spot’, and as such no receipts or long-term records of personnel were kept. Individual names have largely disappeared into the ether, not even finding reincarnation in the sumptuous booklets of reissued CD’s.

It seems however, that particular producers used the same groups of musicians repeatedly. Franz, Oliff, and Wake would use the same orchestra to record Harry Seacombe on Tuesday, the Walker’s on Wednesday, and Dusty Springfield on the Friday. A favoured sticks man was the dapper ‘drummer’s drummer’, Ronnie Verrall.

Something of a legend amongst session circles even then, Verrall would play on many of the Walker’s group and solo sessions, often stretching out on the floor between takes to ease his bad back. Like many of the musicians used at these sessions, Verrall came from a Jazz background, and the techniques of such an education are used to great effect in the context of these ‘pop’ songs. Verrall’s rolling Tom fills, especially on ‘In my room’, ‘Archangel’ and ‘People Get Ready’ would add an unexpected edginess to these tracks. The vivid fills sometimes seem as if they are just about to tumble out of time – they never do. Players like Verrall are typical of the Jazz influence inherent in the Walker’s recordings, a flavour that would add another unique ingredient to an already quixotic mix.

Many of the musicians of this era felt that they had strayed from their original musical calling. But pop music was on the rise and it paid well.

Alan Parker: “I studied classical guitar originally, and I got all the degrees and all the cups and medals by the time I was fifteen. All very nice, but you couldn’t earn a living at it, you know. So I swapped over to Electric guitar. Played with all the big bands in the Dancehalls, Tubby Hayes at Ronnie Scott’s club…Played with Buddy Rich. And you had to learn to sight- read. It was good grounding. I could play anything that was put in front of me.”

If, in 1965 someone had suggested to any UK A&R man that they form and sign up a group consisting of a full classical orchestra, a Jazz rhythm section, plus extra percussion and the odd choir (Male and female), they would have been shown the door there and then. Such a pitch would have been soundly laughed out of the office, well before the further suggestion that three young, impossibly handsome Californian dudes should front such a colossal combo. Three ‘Brothers’ whose own musical interests and experience ranged from Surf, Rock ’n’ Roll, Cocktail Lounge, Broadway musical, Avant guarde and classical. As if this was unlikely enough, the actual drummer of the three wouldn’t drum. Oh, and the lead singer had one of the greatest Ballad voices ever and sounded 20 years older than he was. And they’re called ‘The Walker Brothers’ but aren’t actually related. Or called Walker.

However, through glorious accident and design, by inheriting the three Californians from Mercury and by deciding to invest and promote them as one of their own, this bizarrely attractive mutant hybrid is exactly what Philips had.

Back in the Studio, this wonderful new creature named ‘The Walker brothers’ was being taken for a test run. The supporting cast numbered almost a hundred and among the faceless hordes of hired musicians, it was the players of a still relatively ‘new’ instrument, The Electric Guitarists who were beginning to stand out. Leading lights on the then session circuit were Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, and Vic Flick. Vic Flick would find fame as the man who played the James Bond ‘007’ riff and Wake asserts that Jimmy Page played on at least one Walker’s session. Interestingly, very rarely would the musicians on the record play with the same artists live.

It is also worth noting that in most cases these were just jobbing musicians, living session by session with little thought at the time for posterity.

Both Alan parker and Big Jim Sullivan would go onto play guitar for The Walkers throughout the next decade but at that first meeting, even with the modest hit of ‘Love her’ behind them, the name obviously meant little to them. “I had no idea who they were” admits Parker.

‘Big’ Jim Sullivan, also considered the gig just another job, but even so picked up on something special. “I worked with ‘em right from day one of them coming to England.” He states matter of factly. “We didn’t really know what we were doing. We didn’t know we were laying down history. Who were The Walker Brothers? Nobody until they had hits…I was introduced to Scott going up the stairs of the Philips studios…I remember when I first heard him sing I thought ‘This guys got a great Voice’.

There are some people whose voices don’t suit their face but his did…he was a cool guy in everyway that I could see”.

Alan Parker describes the dynamic at these sessions:

“Scott was very, very friendly and a little bit nervy, a little bit fractious, I suppose. But that was just his personality. But we got on, he and I and John, we got on extremely well and over the years it developed into quite a professional relationship.

On those early sessions, my set up set up then was a little Fender amplifier, a Deluxe reverb. Guitar wise, would have been either a Fender Telecaster a Stratocaster or a Les Paul.

I would usually play the lead guitar but if I was working with Big Jim, we may swap around now and then and he would maybe do it.

Big Jim would play a lot of the Acoustic parts, too and we’d both do the ‘Ker-Chink’ on the offbeat…that would be done on either the Telecaster or the Strat’. I would always take at least three or four guitars with me to the session.”

Big Jim remembers the session slightly differently.

“My first session with them was for ‘Make it Easy…’ You can tell it was me because in lots of the tunes there, especially with Ivor Raymonde, I’d be doing the ‘Ker - chink’! sound on guitar. That was my speciality. That’s why Ivor used me because I did all of the cross- rhythms on electric guitar. When Ivor had a session, I was usually on it.

My amplifier then would have been an Ampeg and the guitar I used on these sessions was called a ‘National’…I’d use a fuzz box when they wanted distortion.

Listen to ‘Make it easy..’ It sounds like there’s two electric guitarists playing two parts but that was all me, recorded live.

I had a footswitch that triggered the tremolo either on or off. Just a pedal. Nothing to it.”

The image of an unflustered Big Jim, pretty much playing his parts as he read them alongside a full orchestra - whilst being recorded live -is an apt microcosm for the whole recording process used for these works. Sound preparation in the dual meaning of the word was a necessity. This discipline would be ingrained in Scott for the rest of his recording career. Speaking decades later, he was acutely aware of the effects of this particular apprenticeship.

“I come from the old school of recording – and I combine it with the new” he would say in the 80’s. “The reason I work this way is because in the early days when I was working at Philips as a co-producer on those records, I had to have everything prepared. So our albums were done very quickly and live, with a live orchestra. So in my mind I always work that way. I always get everything completely in my head before I go into the studio, because there can’t be any mistakes and it helps people work faster”.

While the squadron of musicians brought the music to life in their own infinitely complicated human way, the techniques used to record them were, especially compared to coming developments, fairly basic.

“Those first sessions were recorded on 4-track.” Says Roger Wake incredulously. “I think we went to 8-track in 1968. In both cases when we ran out of tracks –which would obviously happen very quickly on 4 track as the orchestra took up most of the tracks- we would mix the existing tracks onto a new 4 track leaving one track empty for an overdub, usually the vocal. This could continue up to four stages of transfer some times.” “Those first sessions were recorded on 4-track.” Says Roger Wake incredulously. “I think we went to 8-track in 1968. In both cases when we ran out of tracks –which would obviously happen very quickly on 4 track as the orchestra took up most of the tracks- we would mix the existing tracks onto a new 4 track leaving one track empty for an overdub, usually the vocal. This could continue up to four stages of transfer some times.”

In addition “They hardly had any effects on desks then.” States Big Jim. “ They had reverb and that, but that goes without saying, it’s not really an ‘effect’. When I think of effects I’m thinking of flangers, fuzz boxes, and all that sort of stuff, you know, which we used to put on ourselves, with our amps and/or pedals”.

Therefore, to a large extent, even when taking into account the subtleties of mastering and the variables of playback, the eventual sound of the song, as it would sound on vinyl was, by default already there in the room as it was recorded. It came in part, from the Scores and charts brought to life by the anonymous ranks of Brass, woodwind, and strings.

Like animals in the Zoo, each set of varying musicians adhered to a particular stereotype.

“As far as the orchestra went, it was a little bit ‘Them and us’ as far as the string players and the rhythm section was concerned” Says Parker. “The string players generally kept themselves to themselves, the brass were more…jovial.”

Obviously, such sessions were not cheap, as Maus was wont to brag at the time.

“When we make a record, we have a 25-piece orchestra, with brass, a string section, and an occasional Harpsichord.” Enthused the Mantovani enthusiast. “It costs us from £500 to £1000, but we get what we want so it’s worth it.

We don’t go for these beat group sessions that cost under £300. They be all right for those groups but they are hit and miss affairs and definitely not for us.”

Ivor Raymonde scored the deliciously ornate arrangements with little thought for expense. “Never, never, never, ever worried about money ever. Nobody ever said to me, ‘Look, we can’t afford to have ten violins and four violas and two cellos.” You know, if I’d say “Well I think we ought to use sixteen Violins”, they’d say “Go ahead and do it”. Providing the money from a recording point of view didn’t seem to be a problem.”

Much less easy going at the time was the musicians union. The M.U. kept a strict eye on the activities of all its members and in particular those of the producers. Sessions were timetabled to allow musicians ample travelling time between engagements and up until 1972, when rules relaxed a little, overdubbing was all but forbidden.

Gus Dudgeon (Producer of Elton John, Bowie etc) recalls:

“If you wanted to do overdubbing of any sort, you had to seek permission from the MU but it wasn’t always granted. Sometimes we would only get permission to do a vocal overdub if we produced a doctor’s certificate to prove that the singer was too ill at the original session.”

As a result of thus unrealistic ruling, a charade would ensue. For the sake of the orchestra et al, the singer would have to ‘be seen’ singing in front of all present. Rarely would this performance be recorded, the true vocal being recorded after dark and behind locked doors.

For self - confessed insomniacs such as Johnny Franz, Dusty Springfield, and Scott Walker, this was not a problem.

Johnny Franz:

“We’re both nightbirds. Dusty prefers to record at night and we take it from there. We just go on ‘till we’re happy with the result.”

For the young Roger Wake such methods resulted in a bigger pay packet for a harder job.

“I would always attend the vocal overdubs because that meant overtime!” joshes Wake before adding seriously; “But then, your job doing vocals was much harder - dropping in lines and such. We would have to ‘punch in’ - we were the tape ops! The engineer wouldn’t do it! It’s not like it is now or has been for the last 25 years, where as an engineer I’d have a console and a tape machine in front of me and I’d do all the drop- ins. In those days we were all in separate rooms. Pretty hair- raising when doing a drop- in. And even the evening sessions were three hours. “I would always attend the vocal overdubs because that meant overtime!” joshes Wake before adding seriously; “But then, your job doing vocals was much harder - dropping in lines and such. We would have to ‘punch in’ - we were the tape ops! The engineer wouldn’t do it! It’s not like it is now or has been for the last 25 years, where as an engineer I’d have a console and a tape machine in front of me and I’d do all the drop- ins. In those days we were all in separate rooms. Pretty hair- raising when doing a drop- in. And even the evening sessions were three hours.

It was only in about 1967 that this started to shift, when people like Scott and Dusty who were so similar in that they were so particular about their vocals. They had to be ‘perfect’. If they felt they hadn’t sung something properly -even if it sounded perfect to everybody else –we’d have to do it again. Dusty was the worst in the end.

It was horrible! She wouldn’t let anything go unless she thought it was sensational and Scott verged on that but it took him quite a while. Initially his vocals were done quite quickly in three - hour sessions.”

Such nocturnal shenanigans would come later, when Scott in particular, buoyed by commercial success and Franz’s encouragement, would be allowed to peruse his perfectionist aesthetic. For now, the vocals were just another instrument and were recorded as quickly as possible with little fuss and nerve racking consequences.

“It was a pretty frightening experience” says Maus with typical West coast understatement. “The way we recorded all of the early things we did…you had to be in the position of knowing what you were going to do…Scott and I as a duo, didn’t work on separate microphones. Any of the balances and things between ourselves came from ourselves…”

Dave Dee speaks of similarly primitive experiences. But for the trained musicians at the sessions, such hit and run tactics were less of an issue.

“As a guitarist, I didn’t find recording live scary…” states Alan Parker. “You had such a good working relationship with the other musicians and with the M.D.’s and producers…

To be honest, that’s part of the reason why you were booked, you weren’t fazed, and you contributed. You didn’t just switch the amp on and go ‘Ker- chink’, you used your brain and inventiveness, your imagination.”

Scott and John were hardly novices either and with the support and planning of all involved, ‘Make it easy on yourself’ took just forty minutes to record..

Ever economical, Philips ensured that Franz used every spare minute of allotted studio time. When the sessions had gone well and finished under schedule, there was always something else that could be squeezed in..

Pirate DJ Dave Cash was an early benefactor of the Philips Thrift.

“As for the jingles for our ‘Kenny and Cash show’, I believe they recorded them during their first session”. Says Cash. “My contact at Philips, Paddy Fleming, told me it was during the session for ‘Make it Easy on Yourself’ that they recorded ‘em. We got a ten- inch tape out on the boat with ‘lotsa love from The Walker Brothers’ written on it. The jingles were not orchestrated, just their wonderful voices with an organ behind ‘em. Quite heavy Echo as I remember.”

Sessions for the album were staggered to accommodate a short UK tour and various promotional duties. This meant that a full days recording would often follow a chaotic gig the night before, a circumstance that would, depending on the songs scheduled to be recorded, be both a help and a hindrance as far as the voice went. Scott was keen to bring his Gold star studio experience to Britain and would soon be a dominant force both on the studio floor and in the control room.. Sessions for the album were staggered to accommodate a short UK tour and various promotional duties. This meant that a full days recording would often follow a chaotic gig the night before, a circumstance that would, depending on the songs scheduled to be recorded, be both a help and a hindrance as far as the voice went. Scott was keen to bring his Gold star studio experience to Britain and would soon be a dominant force both on the studio floor and in the control room..

Having recorded the sublime ‘A girl called Dusty’ the year before with the same team that the Walker’s were now using, Dusty (or ‘Dusts’ as Franz called her in the studio) had, to some extent, already gone through what Scott was about to.

“I was asking musicians to play sounds they’d never heard before.” Says Dusty, “The guys I had to work with were all playing standard basses. I was actually the first person to ask them to play a Fender Bass. I was a stickler for getting it just right…I kept saying ‘No, that’s not it’ and So on.” She remembered in the late 70’s, eerily echoing Scott’s same approach..

“I was…wanting to cop Phil Spector’s sounds and I knew that I could. I wanted to be The Crystals and Darlene Love and knew that there was going to be a space for that in this country because it hadn’t hit here and I definitely knew that that wall of sound thing could be adapted for England and I was the one to do it…”

Franz would not have allowed Scott’s input if he had doubted the young singers ability and vision. Engel was allowed to work beside Franz in the producer’s chair but he knew better than to take it any further.

“I picked 75% of the material, because I was a kind of ‘producer in disguise’ in those days, for some reason. There was a situation there.” Scott told Irish Journalist Joe Jackson some 30 years later. “It was a personal situation, whereby I wasn’t getting any credit for – but I actually did – most of the planning and stuff there. All the stuff that was brought in through Franz was fielded through me finally to the end, unless somebody brought in an unusual song. We worked very closely together, John Franz and I. It was very 50/50. He had a lot of knowledge about how to get an orchestra down in a classical sense. Of course, I had the youth behind me and the excitement of wanting to get it down with everything on, you know. Naturally, it all had to be done at once. We weren’t lucky like Phil Spector – we didn’t have the same kind of finance. For instance – at the beginning – Phil would be able to go over to the rhythm section on one day. If he didn’t like it on that one day, he could take the rhythm section the next day, or the next and build and build, all on over dubs. We had to do it all at once, – everyone playing in the studio –which I think is a hell of a lot more exciting. If you listen to our records in comparison – that’s the one thing, because the musicians ‘got off’ and the sound is just barrelling down on you, you know. It could have been better recorded - but that was the problem you see – recording all at once, you can’t.”

Dusty Springfield also kept her ‘secret’ role hidden from the public.

“The magic of my situation with Johnny Franz was that he allowed me the freedom to follow my enthusiasm.

I never took the producers credit for two reasons. For one, he (Franz) deserved it and I was grateful. And then there was the calculating part of me that thought it looked too slick for me to produce and sing.”

Roger Wake was there from beginning to end and he remembers it as less cut and dry.

“Scott wasn’t at all visible to me as a co-producer during the early sessions. Perhaps he had spoken with the arrangers beforehand.” Wake muses.

“Maybe he was more active later on – certainly - but during those early sessions, he was just the singer. Johnny Franz was totally in charge. And what Johnny said went. With all his artists. It was Dusty Springfield and Scott that changed that with Johnny but they were the only two that ever did get away with disputing whatever Johnny Franz’s decisions were.”

This was a rare evolutionary step within the world of popular music. Not only did people like Scott and Dusty have what it took in the ‘Star’ stakes, but they were also diligent, articulate, and professional conceptualists. Each could have made it either side of the recording console either as just a singer or a producer. The Walkers and Scott in particular were about to become pop stars in a way never known before.

Wake witnessed this new phenomena first hand: “They were the new kids on the block as it were but the singing was very impressive, the songs were great and so were the arrangements…they couldn’t fail, really.”

|